mr mizuno's finest knives

JAPAN'S BEST BLADES // SAKAI

If you’re in the market for a good knife, forget Chef’s Warehouse, forget Tokyo’s Kappabashi Street – you need to go to Sakai. Just a 20-minute train trip along the Nankai line from Osaka, this little port town is more than just a seaside suburb, it’s the home of Japan’s best knives – so highly revered that 90 per cent of Japanese chefs are said to own a knife from Sakai.

The history of the craft is long and detailed, but stick with me, I’ll keep it brief. It started in the 4th century, when a cluster of more than 100 giant forest-covered tombs were constructed in Sakai. Known as kofun, these impenetrable burial grounds were built as a resting place for emperors, empresses and their treasured valuables.

The largest in Sakai is the Nintoku kofun (above). Built for Japan’s 16th emperor, Nintoku, and spanning 486 metres long (bigger than some of the pyramids of Giza), it’s thought to have taken more than 15 years to build with more than 6 million labourers. Building the country’s largest tomb required the country’s best craftsmen and Japan’s most trusted artisans were brought to the city to help produce the tools needed for the job, including blacksmiths.

Fast-forward a few centuries, and Sakai was now the centre of production for Japan's best samurai swords. By the time Portuguese traders arrived in the 16th Century bearing guns and tobacco, Sakai was the only place with the sharpest knives necessary to cut the tobacco leaves; short and fat rectangular-shaped blades were crafted specifically for this use. After the Meiji Restoration and the end of samurai rule, swords were no longer in such high demand. The craftsmen focused on creating kitchen knives – single-edged blades that are so sharp and strong they slice through meat, fish and vegetables with almost no damage to taste and texture. Sakai knives began to grow a strong and trusted reputation.

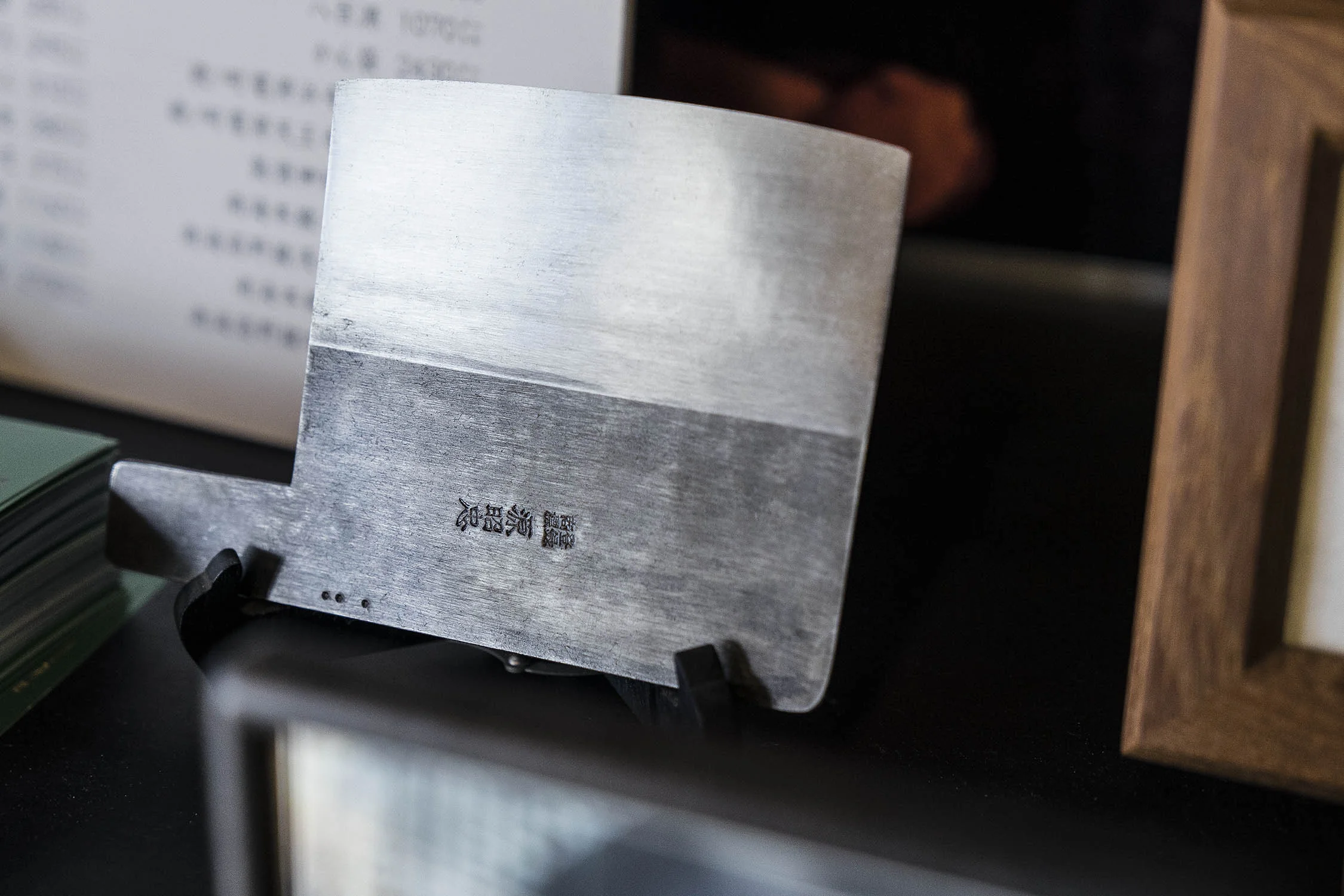

I've been interested in Japanese knives for a while, and I was keen on seeing the process from behind the shopfront. We set up a time to meet Jun Mizuno, a fifth-generation knife-forger at the Mizuno Tanrenjo knife workshop. The Mizuno workshop began in 1872, when master blacksmith Torakichi Mizuno began crafting chef’s knives for local cooks. Jun showed us into the old Mizuno workshop, where dusty katana swords hang and blades for slicing up whales were still on show. It's Jun's wife, Nanako, that belongs to the immediate Mizuno family with Jun continuing her father's tradition for the past eight years. "I like the process – making something from nothing," he says.

Jun hops into his office, a dug-out, earthy hole in the ground next to a flaming 850°C oven and a 50-year-old mechanised hammer. “This is a part of my body,” says Jun of the hammer, as he deftly switches from thrusting the steel blade in the oven’s flickering flames to beating the red-hot metal into shape with the machine. After a few rounds of shaping, a layer of soft iron is pounded on top, joined using a sprinkle of iron powder. “I’m making a single-edged sashimi knife, this is only made here in Japan,” says Jun. The flat surface of a single-edged blade allows for a steeper blade angle, a sharper knife, and a cleaner cut.

Jun works back and forth between the oven and the hammer until the shape of the knife is just right. Next comes the hardening process, yakiire, something that takes a long time to get right. “I can make 15 knives in one day, but this [yakiire] process takes four days,” says Jun. The blade is steadily fired in an oven from 760°C to 800°C, before it’s quenched in a 40°C water-bath to quickly cool and harden.

“The temperature is very difficult to control,” say Nanako. “If the heat is too high, the steel isn’t good. But if it's too low, the steel and iron can't combine – so it's very difficult.” Jun can tell if the temperature needs adjusting based on a quick glance at the fire and the colour of the metal. His intuition guides much of the knife-making process, including hammering just the right shape and thickness out of the metal. "Sashimi knives must go evenly from thick to very thin – I just look, I can feel it,” he says.

The blade is done, but Jun’s knife is not yet finished. After the forging process the knife will be taken to a knife-sharpener to be polished and sharpened, and another craftsman who carves and fits the specially-made wooden handle. The whole knife-making process requires a whole ecosystem of craftsmen to make the one tool, something we were to learn about on a larger scale on our next trip to Sakai the following week. [read part two here]

Photography: Leigh Griffiths

Words: Eloise Basuki

All words and images are under copyright © 2019 strangertalk.co